Catalogs

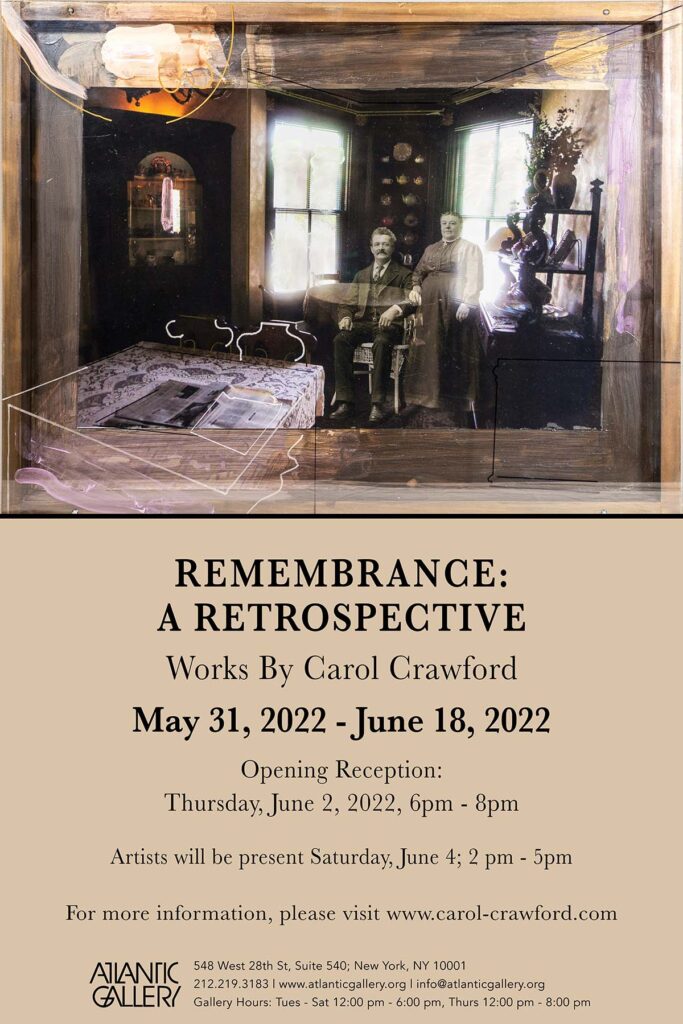

REMEMBRANCE: A Retrospective 2022

Dichotomies 2018

Transfigurations 2016

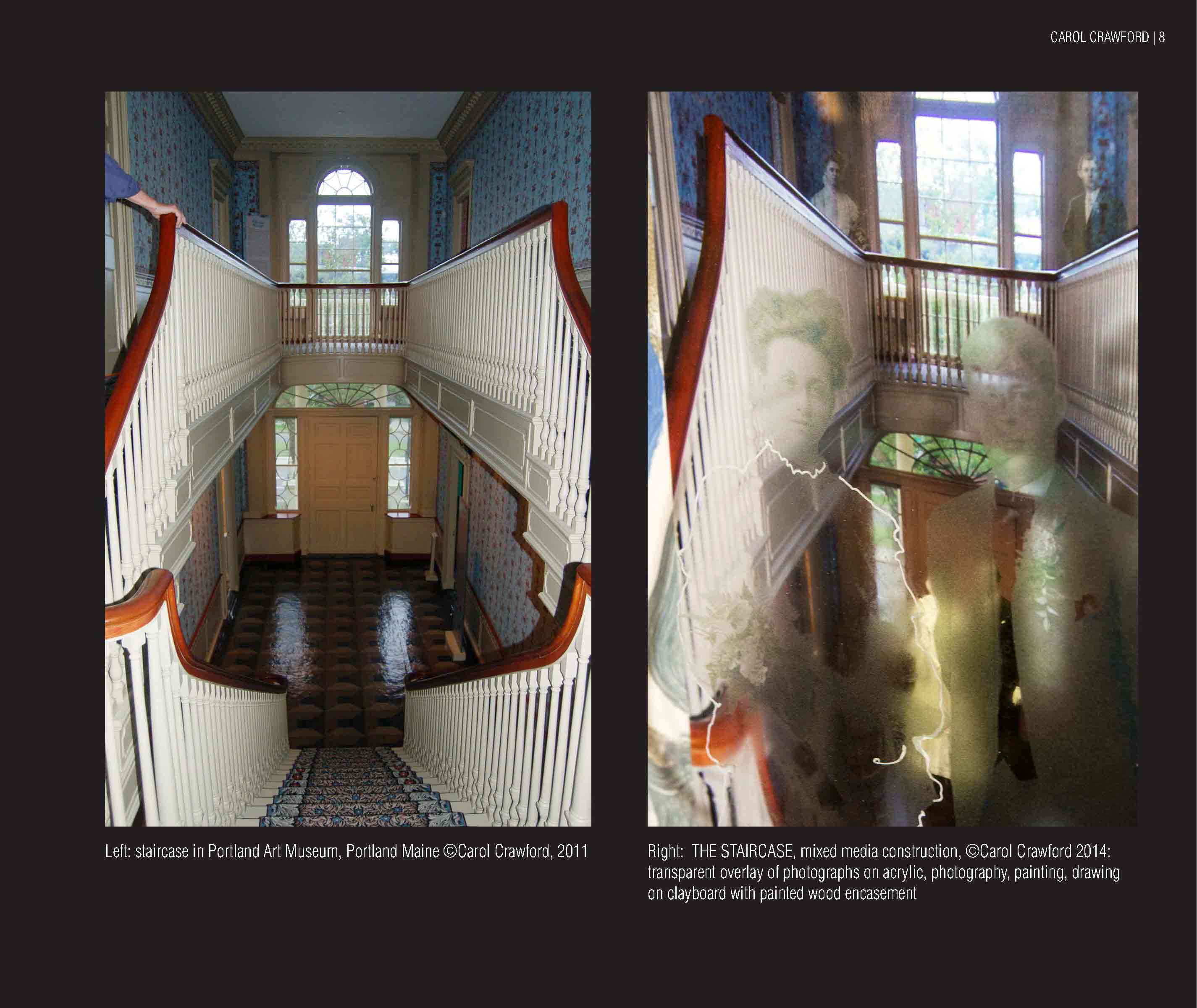

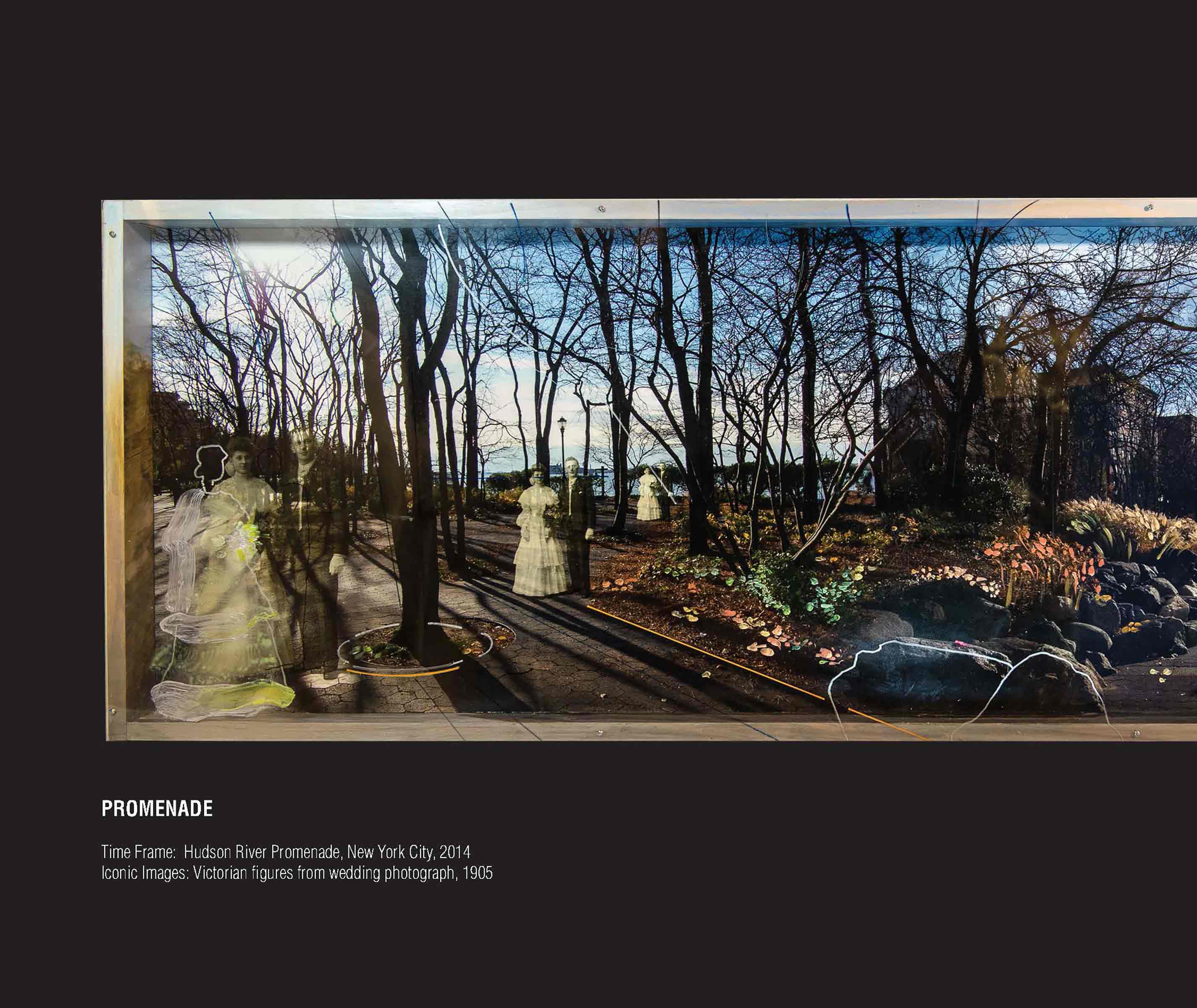

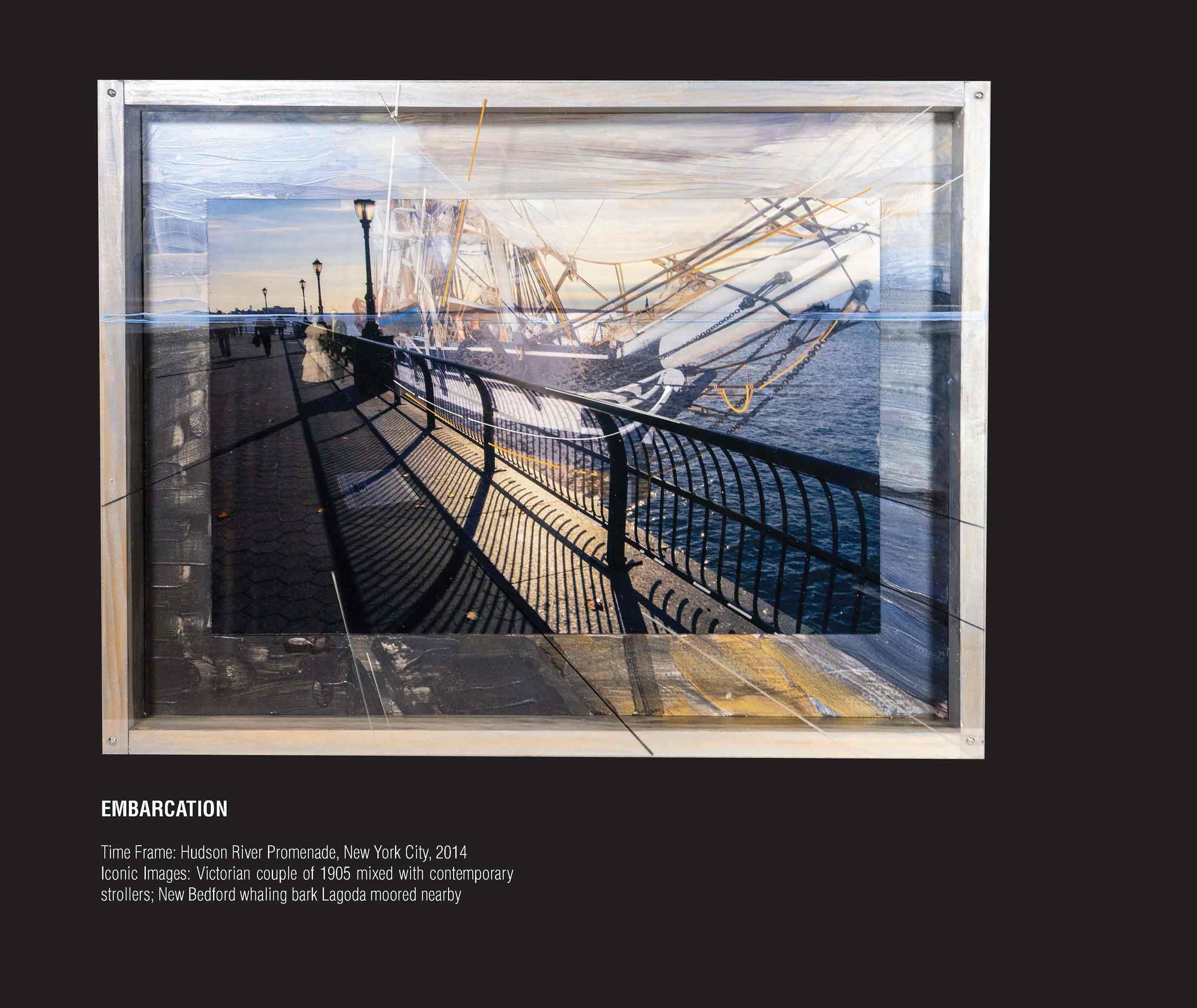

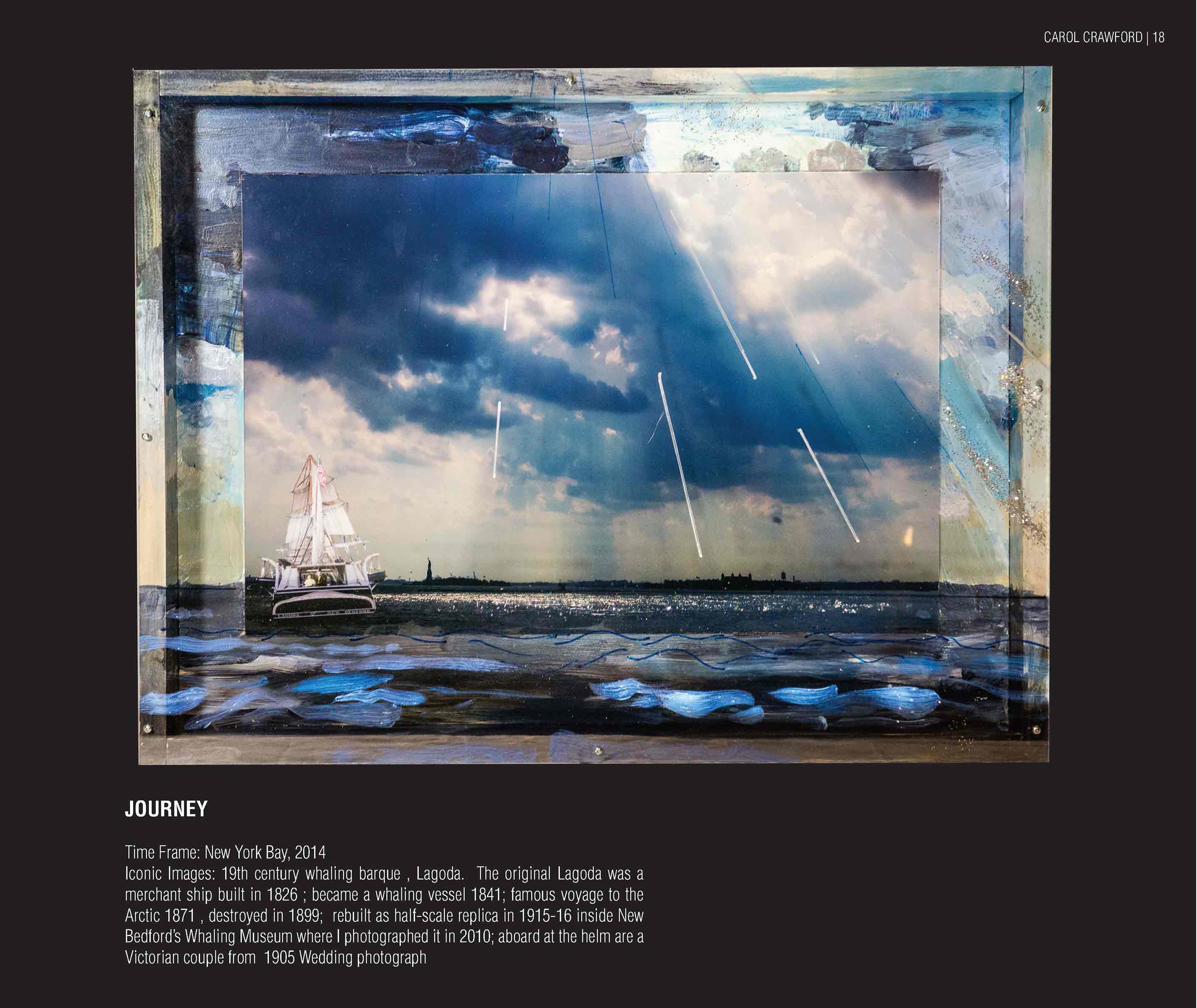

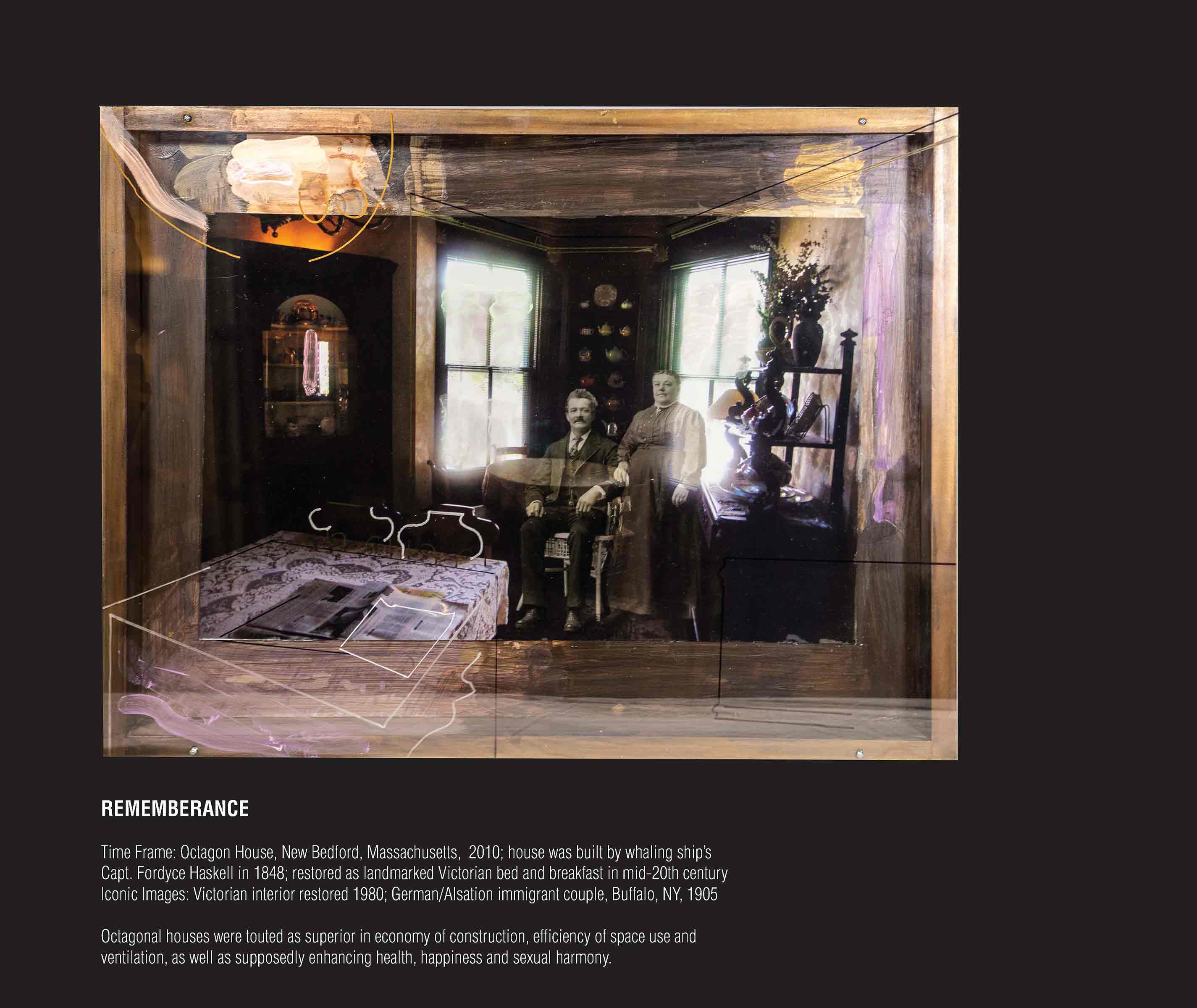

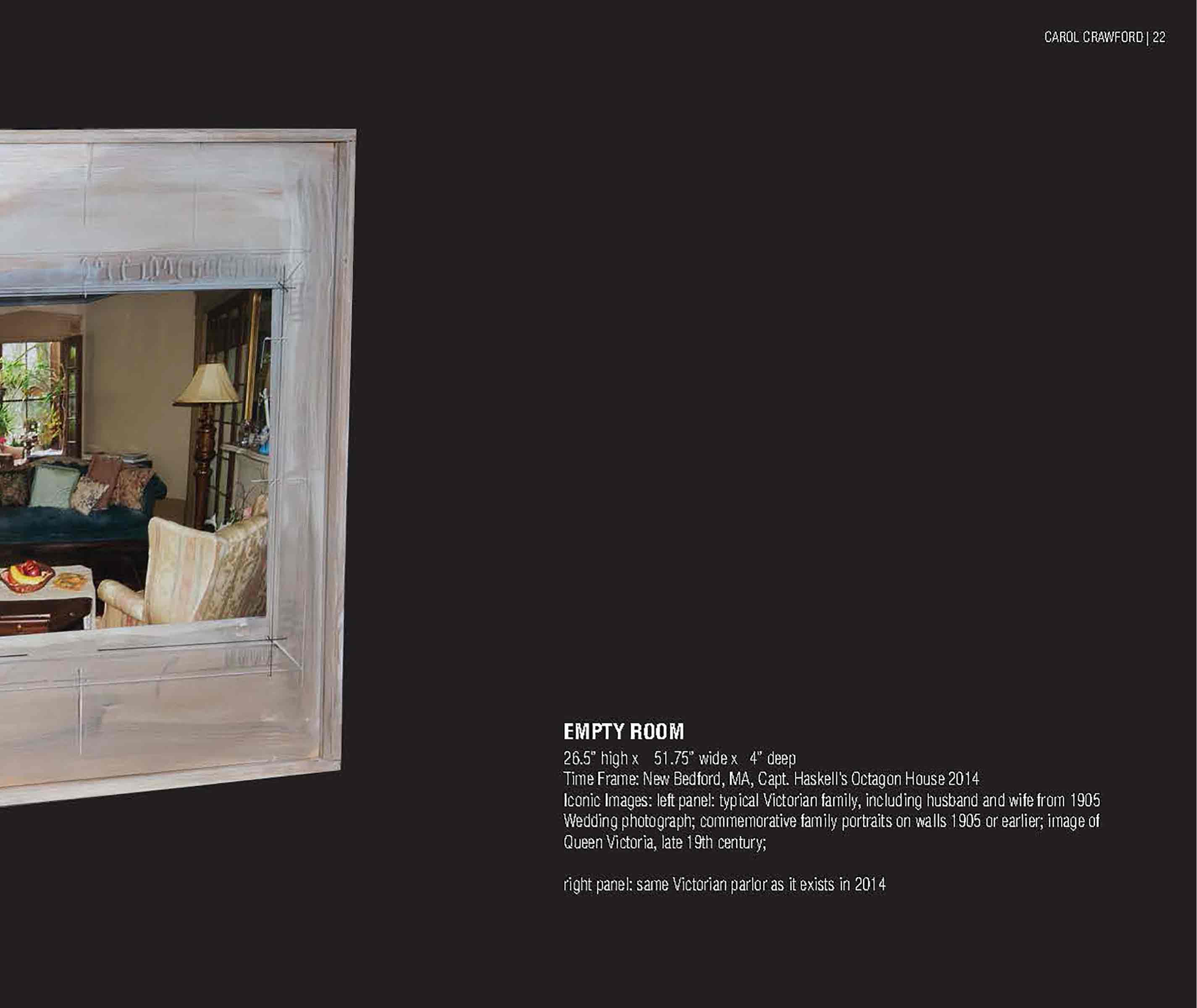

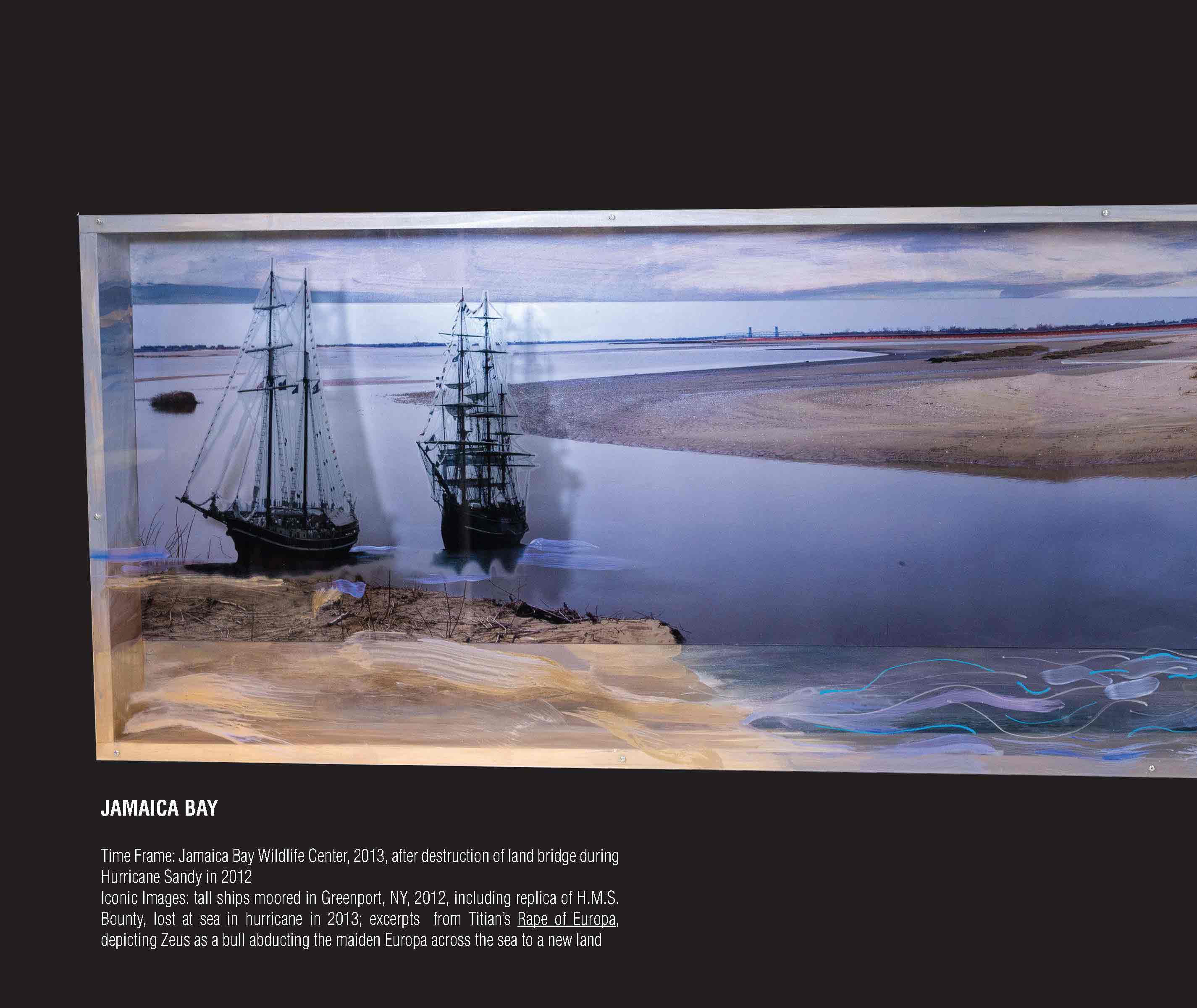

Time Frames 2014

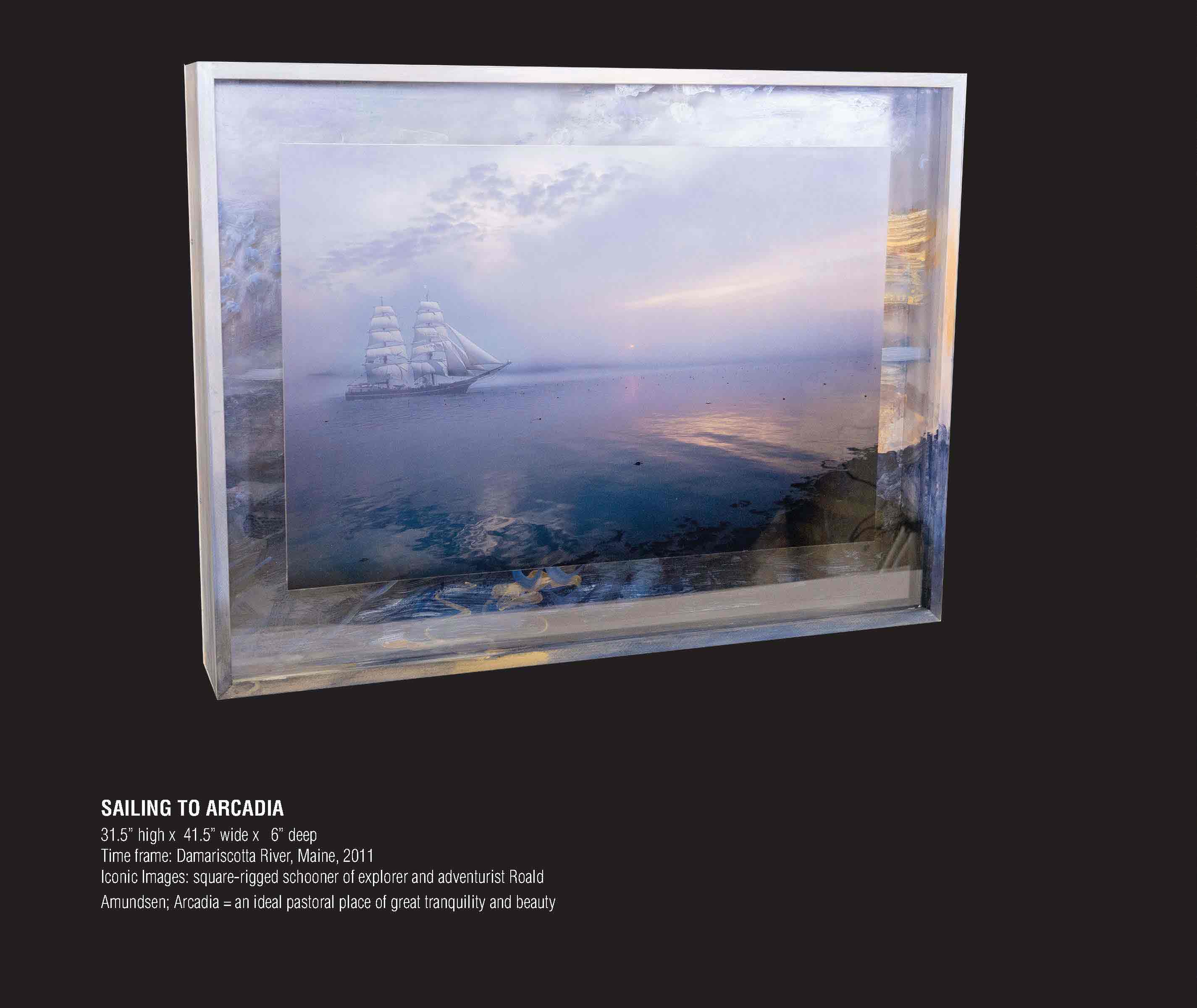

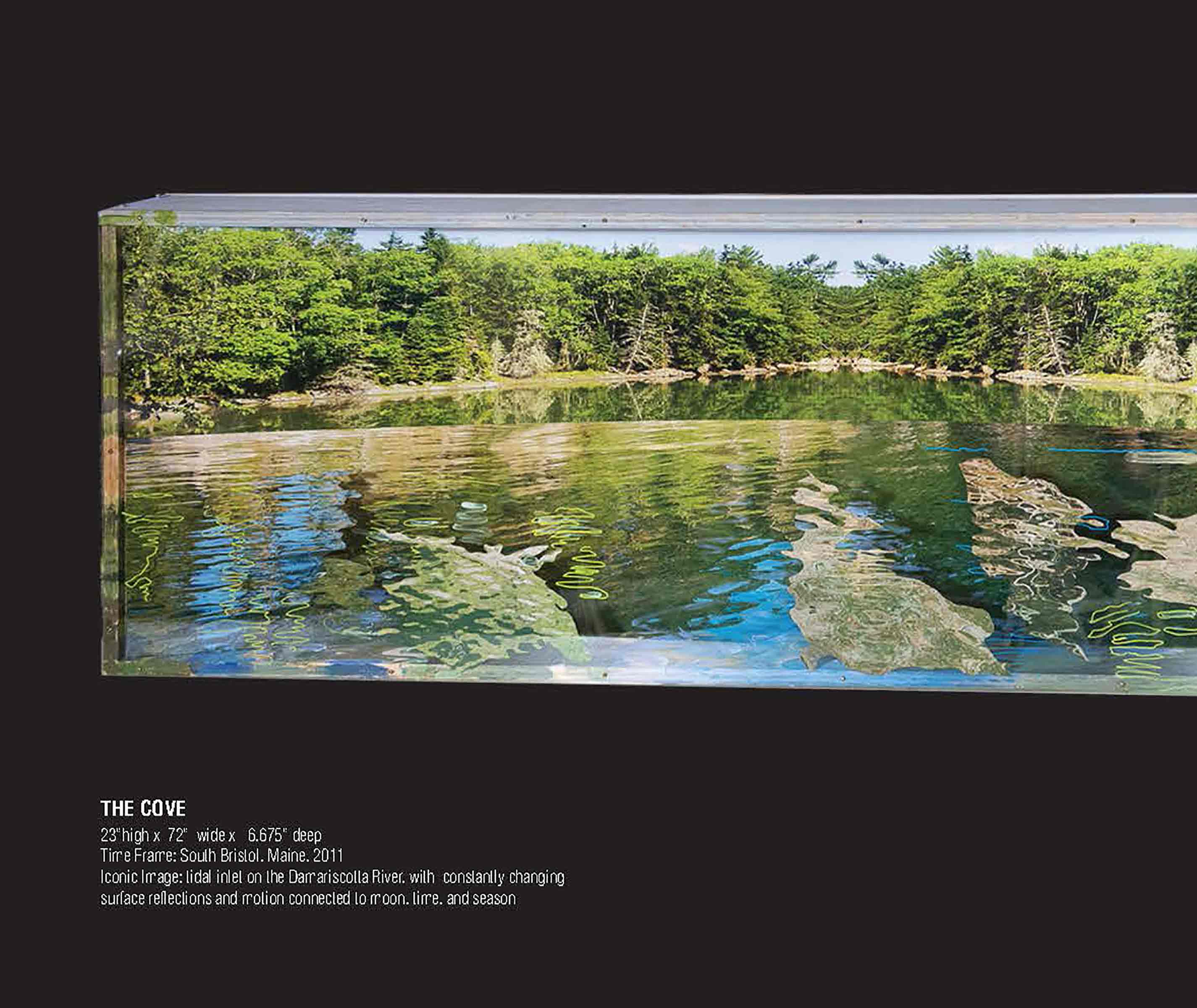

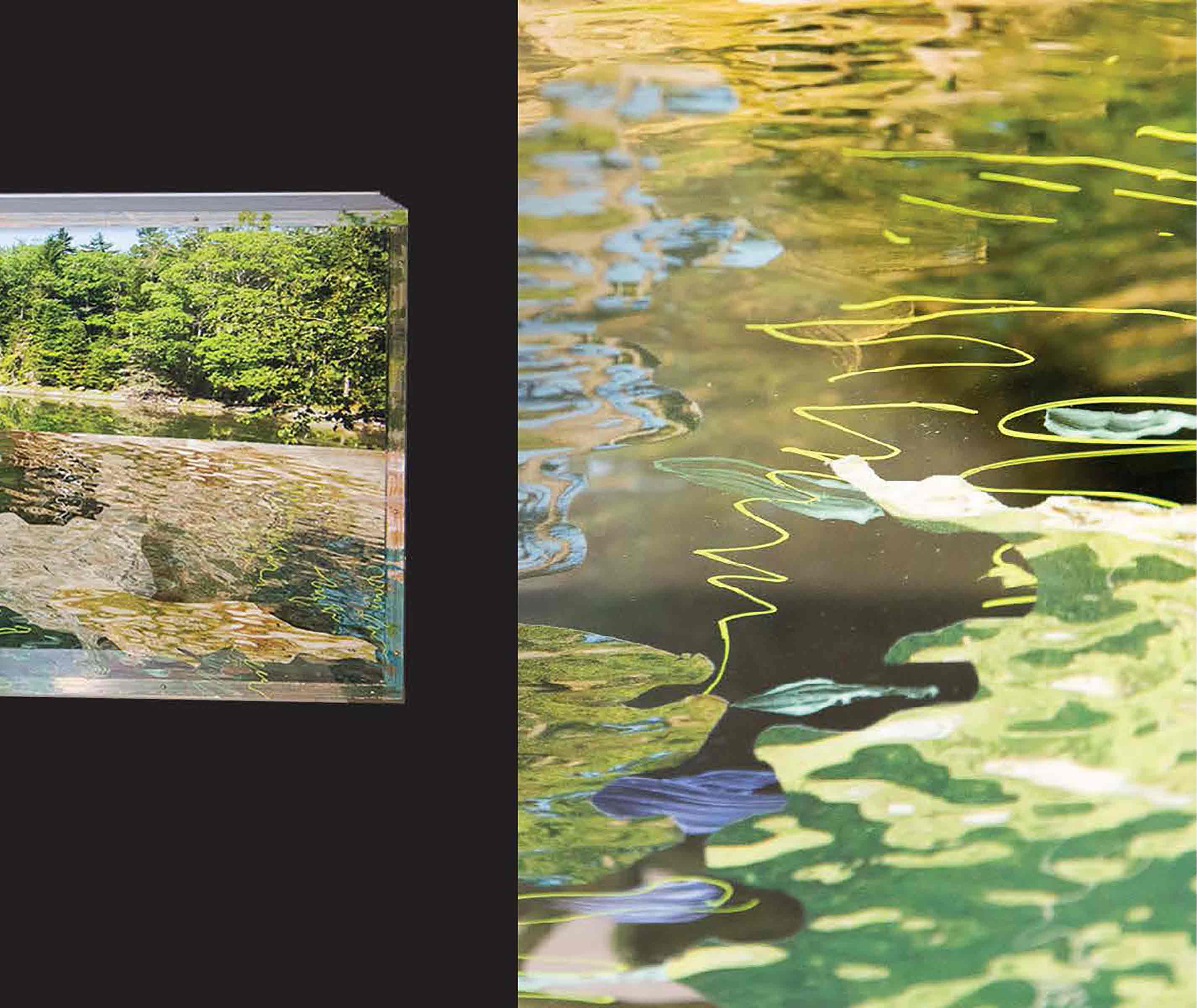

Reflections 2012

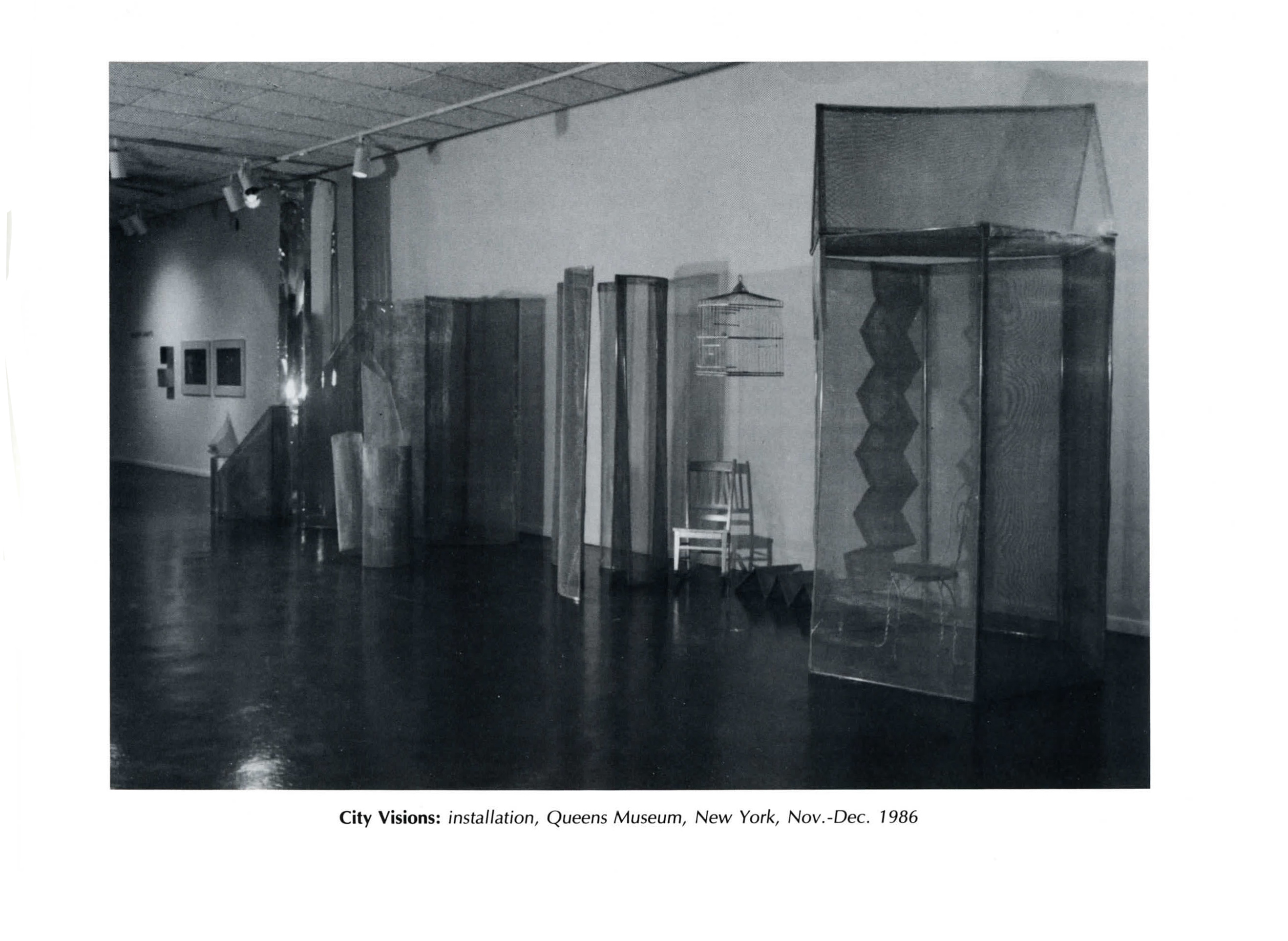

City Visions 1988

The Unsettling Art of Carol Crawford

It is well over a century since the struggle of artists against convention became official with Louis Napoleon’s sanction of the Impressionists in their Salon des Refuses of 1863. Since then, the art of the avant garde has continued to cause sharp reactions, from raised eyebrows and snickers to outcries and scandal. At the very least, we are overwhelmed by the variety of styles, trends, materials, and modalities that art has taken, and never more than at the present. At the most, artists seem to have searched deliberately for ways to provoke shock and outrage, blasting convention with aesthetically uncongenial materials and repugnant or unintelligible subject matter. The artistic process is further confused in our own day as art exhibitions are co-opted by mass culture and turned into public spectacles and extravaganzas, while aesthetic issues are confused with the high finance of the art market. Where is all this leading? Is the condition of the art world as chaotic as it appears?

With all the attacks, defenses, and manifestos of modern art, solutions seem easier than resolutions. There are many answers but little agreement. Yet artists continue to work and art continues to appear, oblivious of or confrontational toward the forces of fragmentation. Some perspective seems to be needed, and since the inner eye may see only its own image, perhaps we can sense direction here by looking at art as part of the larger social picture. D.H. Lawrence once called artists “the antennae of the race,” and he was not the only one to grasp the place of the arts in the vanguard of society. From this vantage point we see the artist not only mirroring the visible world of different times and places but reflecting how people grasp their world. And not just reflecting that awareness, but sensing its direction and leading it forward. With change now endemic in modern society, we find it difficult to lay hold of our elusive reality. Perhaps it is here that we can discover the artist’s social role: To confront that sense of things for which we have no easy concepts, to articulate a world we have not quite apprehended. In exploring what is not yet known, can art unsettle us to the point of understanding?

The traditional model of seeing the world with the dispassionate and objective eye of a spectator, attentive but distant and unimplicated in the processes it observes, stands at the base of our scientific understanding of the world . Rooted in the contemplative idea l of classical Greece, this model returned with new force in the seventeenth century. It was incorporated during the eighteenth century by Shaftesbury and Hutchinson in England and by Kant in Prussia to become the framework for modern aesthetics. The disinterested contemplation of a work of art for its own sake alone became the standard of appreciative experience. This principle continues to rule the traditional aesthetics of academic circles, even though artists have long since left it behind.

In fact, it is precise lyth is change of direction that the Impressionists initiated, using the eye of the viewer to combine and mix the spots of pure color left by the brush of the Pointillists and, more generally, to revel in the sensuous surfaces and light of the pleinair painters. So began a new phase in the workings of art, for the innovation of the Impressionists far outlasted their techniques and their age. We can trace a continuing development of this approach to experiencing art. Aesthetic distance has been replaced more and more insistently by an active involvement of the viewer in the work of art, a tendency that cuts across all the arts. In painting, a succession of movements has appeared that draw on the contribution of the perceiver: dada, that deliberately confounds the viewer’s ideas and responses to art; surrealism, that draws on oneiric forms and preconscious associations; optical art, that forcefully engages the eye in form ing its shapes; color field painting, that overwhelms the spectator with its sensuous surface and vibrant color relations; abstract expressionism, that evokes a subjective complement to the painterly image; unexpected assemblages and inviting environments-the list is as long as the history of modern art.

What the arts seem to be showing us is that a major shift in our sense of things has been under way during this century and a quarter, a change that underlies the searching eye of the contemporary artist. It is, in fact, that moving eye and the body it inhabits that have broken the barriers of conventional art. We have relinquished that classical stance of the contemplative beholder and taken in its place the engaged activity of participatory experience.

For the artist now requires the collaboration of the beholder. Aesthetic distance has been left behind and the viewer is now totally implicated in his work. I call this condition aesthetic engagement, the participation of the viewer with the art object so that what occurs is a collective product, a common result of the contributions of the artist, the art object, and the viewer. We ca n no longer look at art disinterestedly, then, as the tradition would have us do. We are instead vitally interested, not necessarily for practical ends but with an involvement that requires us to be actively engaged and that leaves us vulnerable to the forces of art.

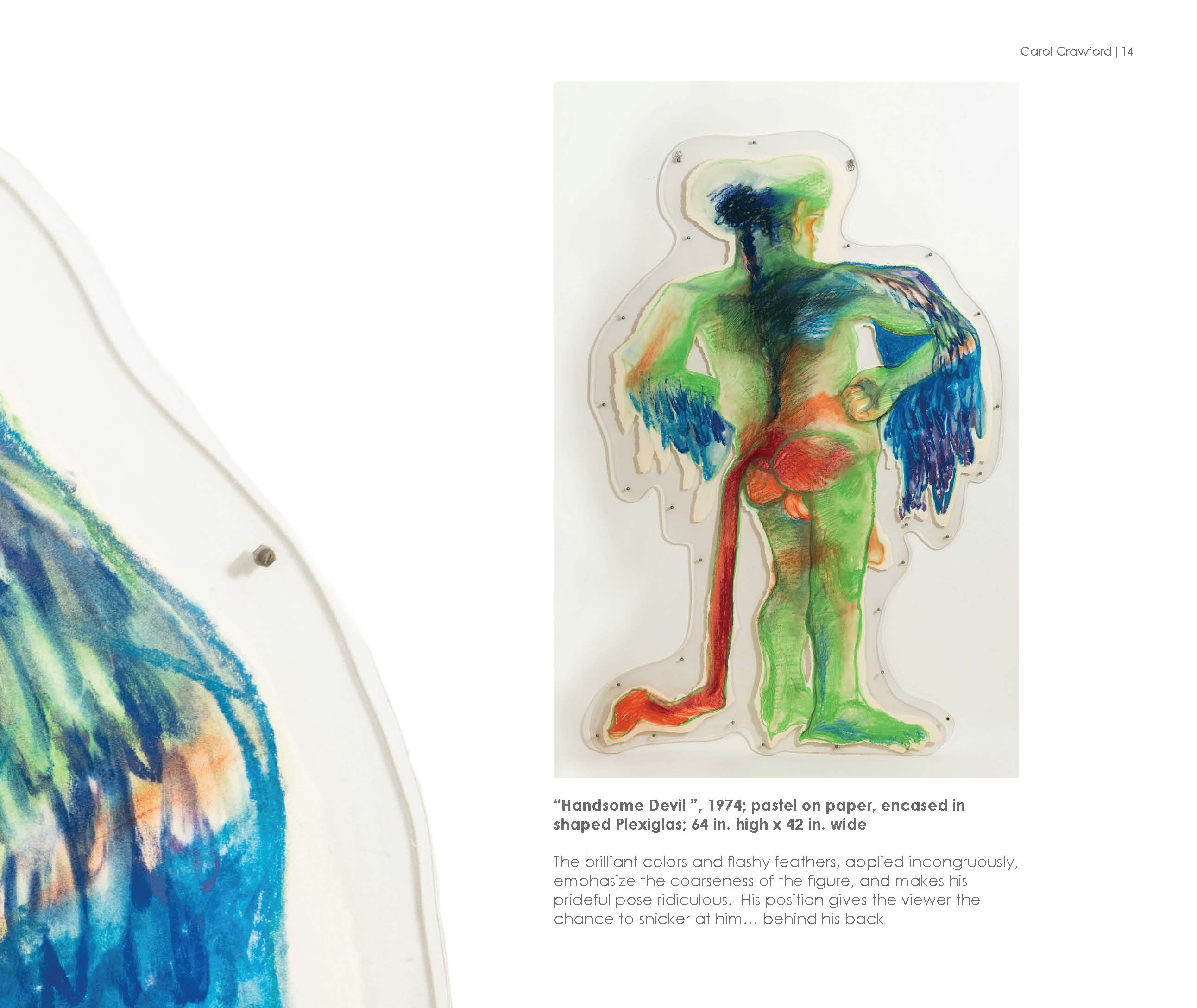

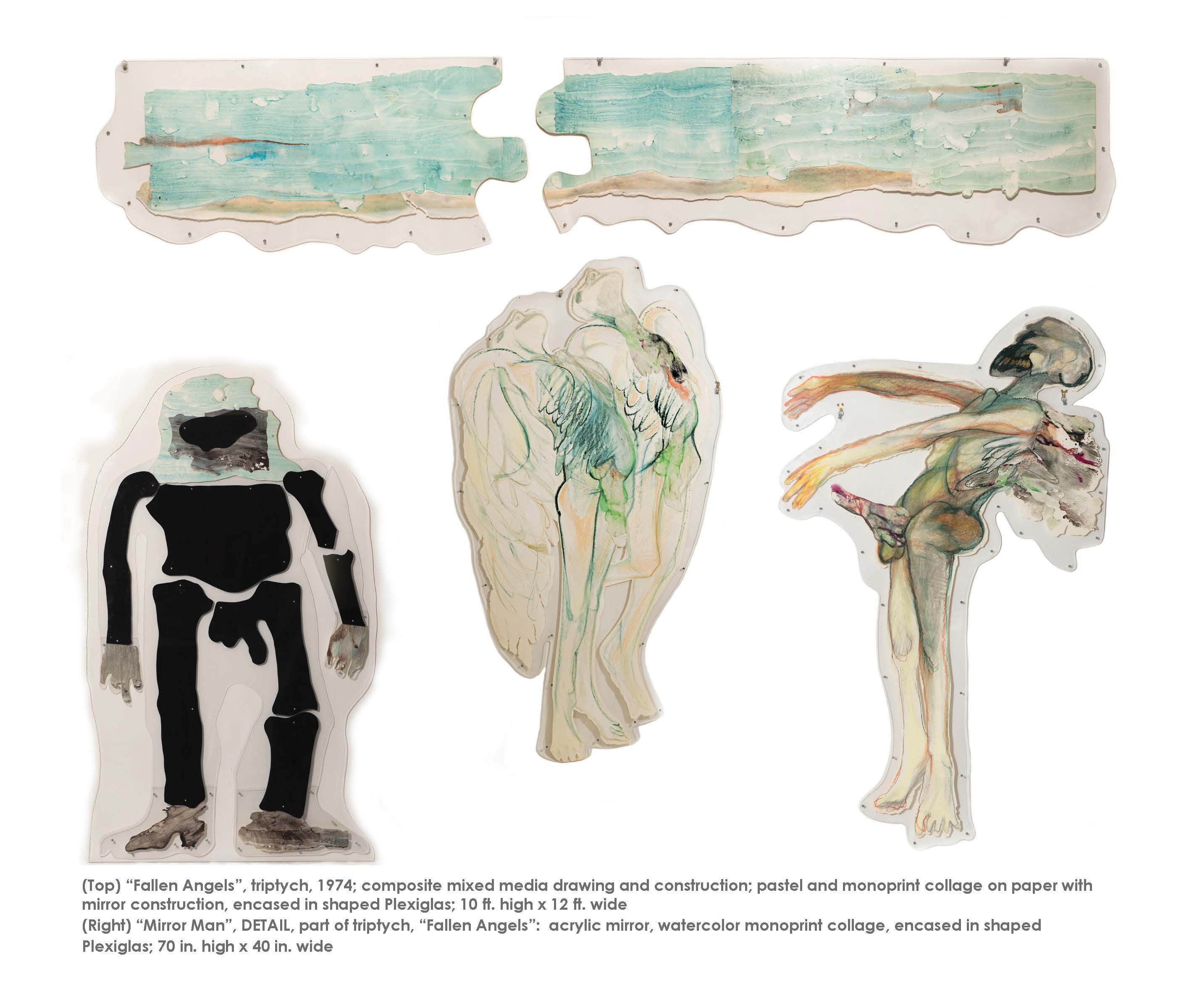

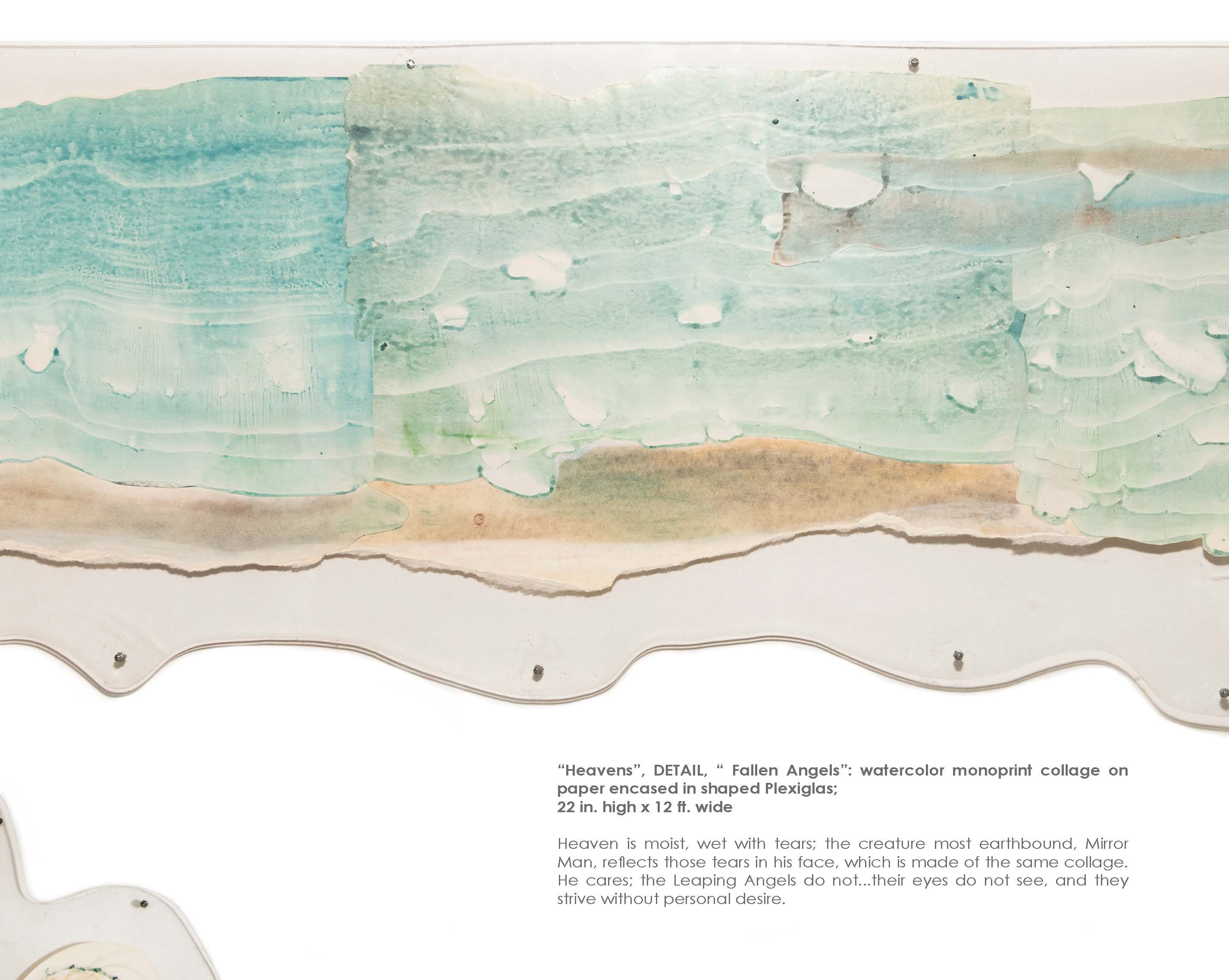

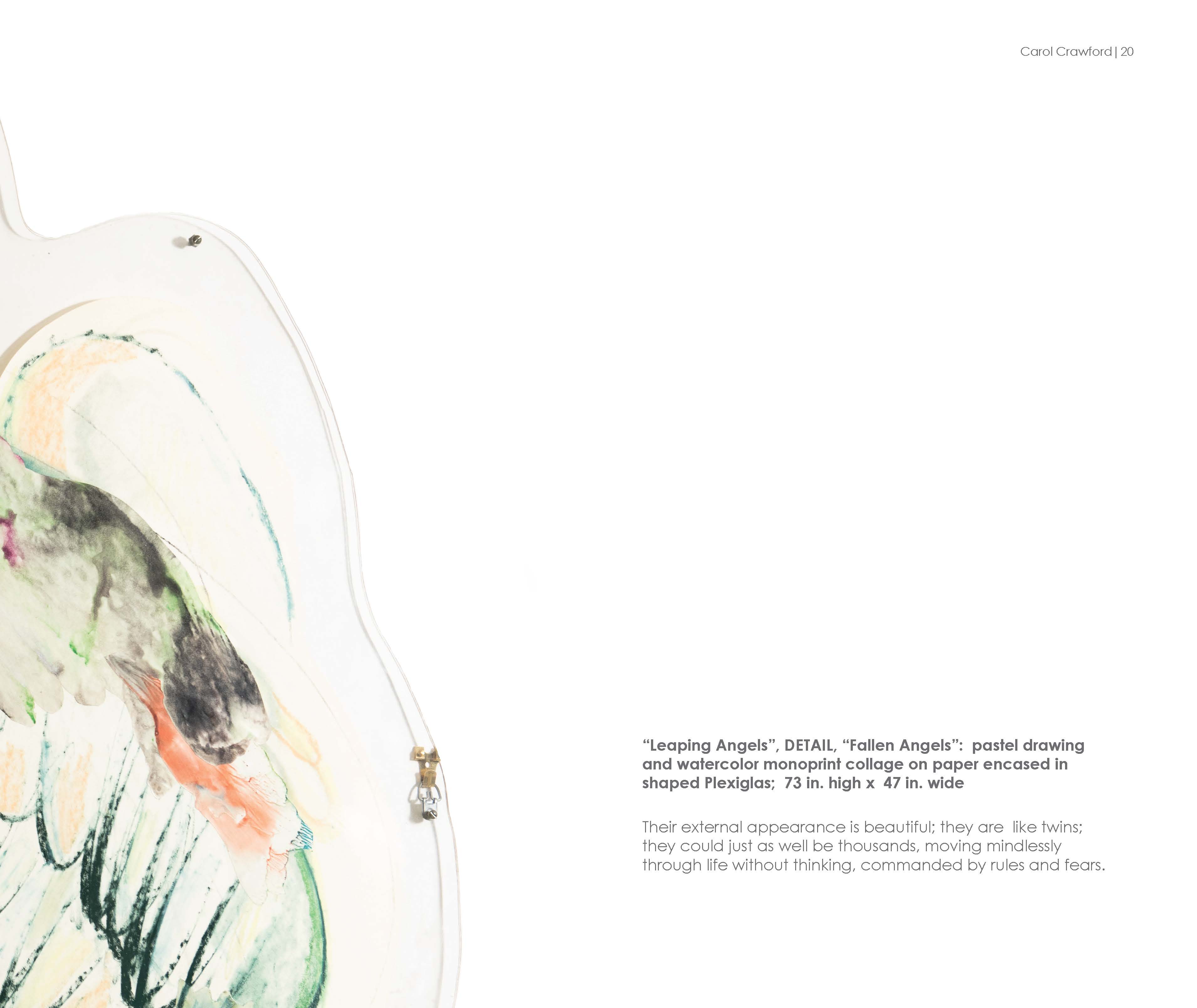

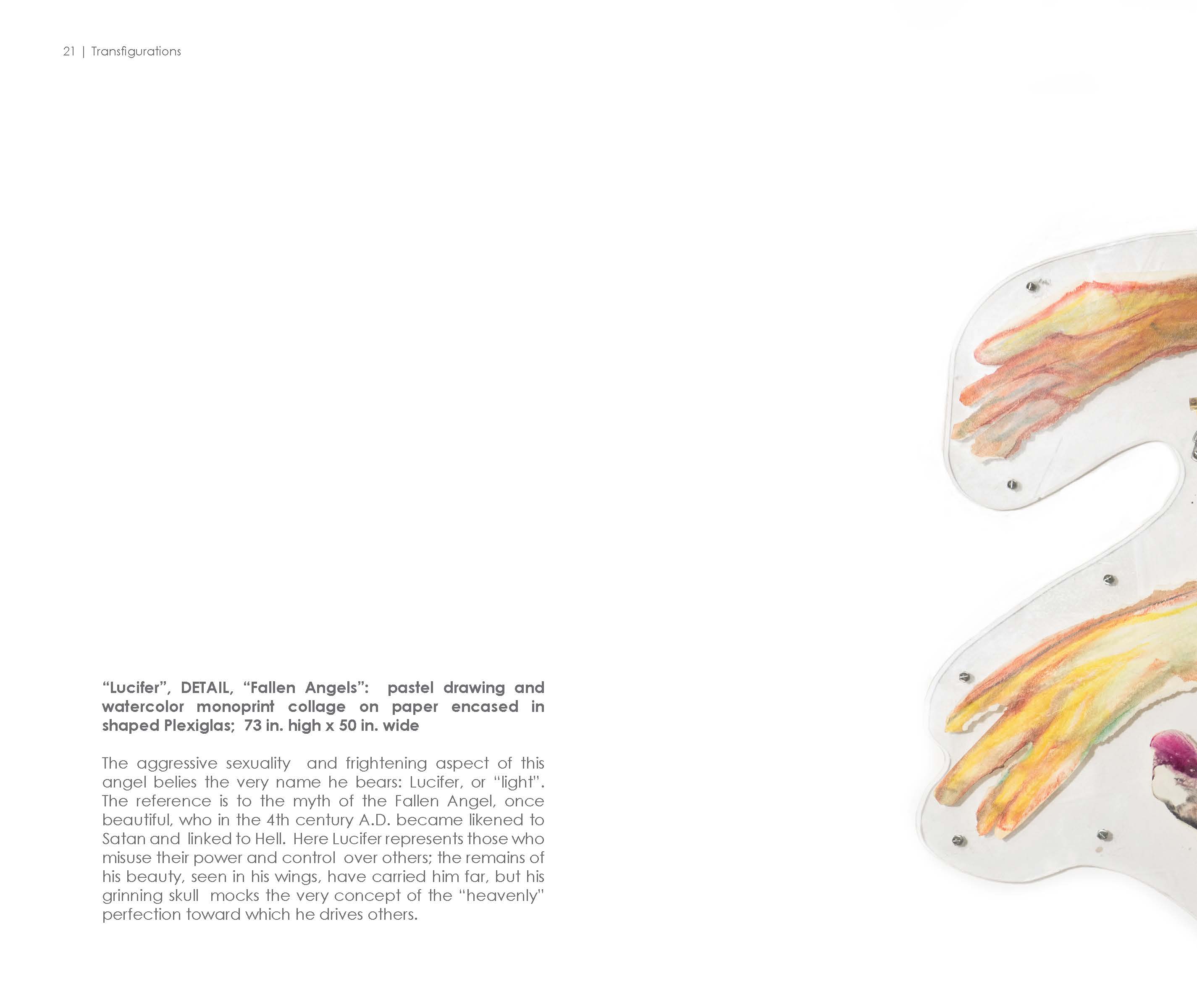

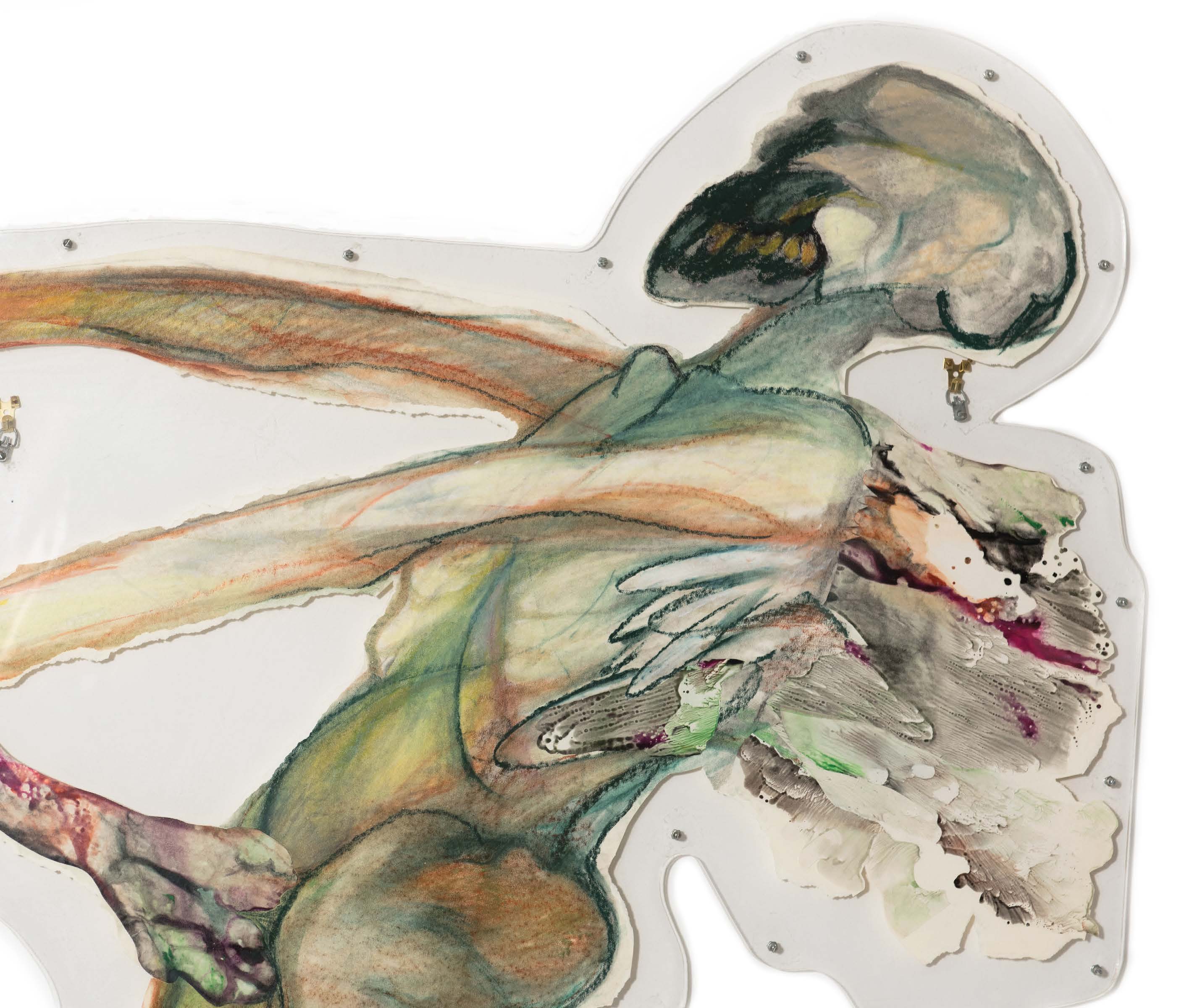

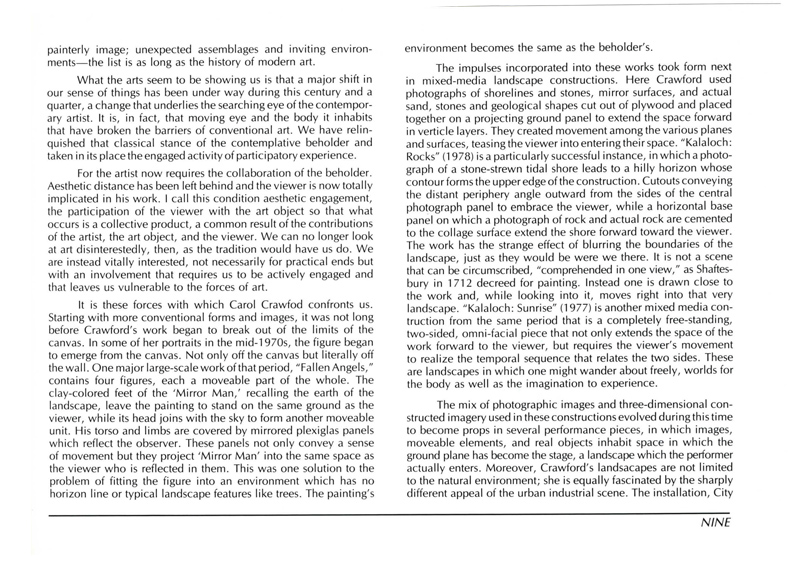

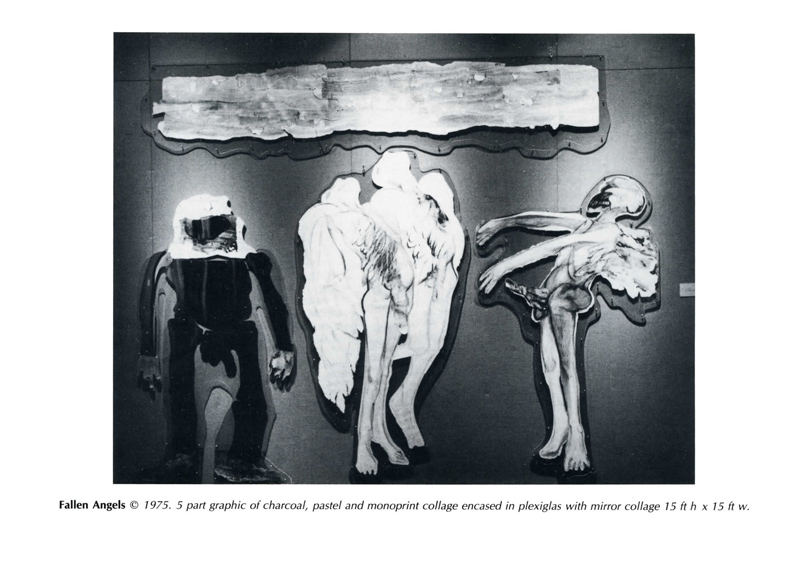

It is these forces with which Carol Crawfod confronts us. Starting with more conventional forms and images, it was not long before Crawford ‘s work began to break out of the limits of the canvas. In some of her portraits in the mid-1 970s, the figure began to emerge from the canvas . Not only off the canvas but literally off the wall. One major large-scale work of that period, “Fallen Angels,” contains four figures, each a moveable part of the whole. The clay-colored feet of the ‘Mirror Man,’ recalling the earth of the landscape, leave the painting to stand on the same ground as the viewer, while its head joins with the sky to form another moveable unit. His torso and limbs are covered by mirrored plexiglas panels which reflect the observer. These panels not only convey a sense of movement but they project ‘Mirror Man’ into the same space as the viewer who is reflected in them. This was one solution to the problem of fitting the figure into an environment which has no horizon line or typical landscape features like trees. The painting’s environment becomes the same as the beholder’s.

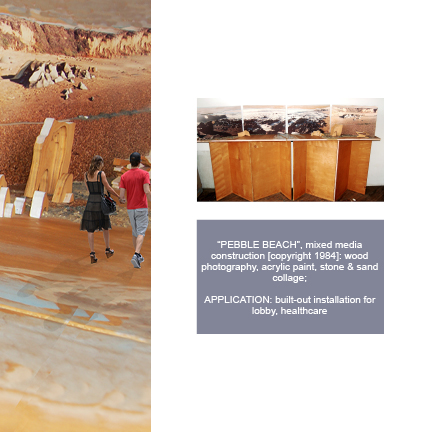

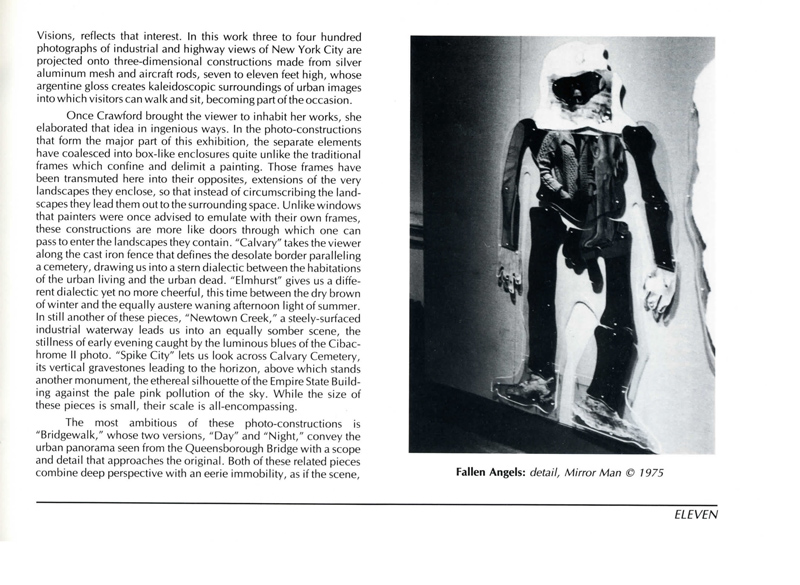

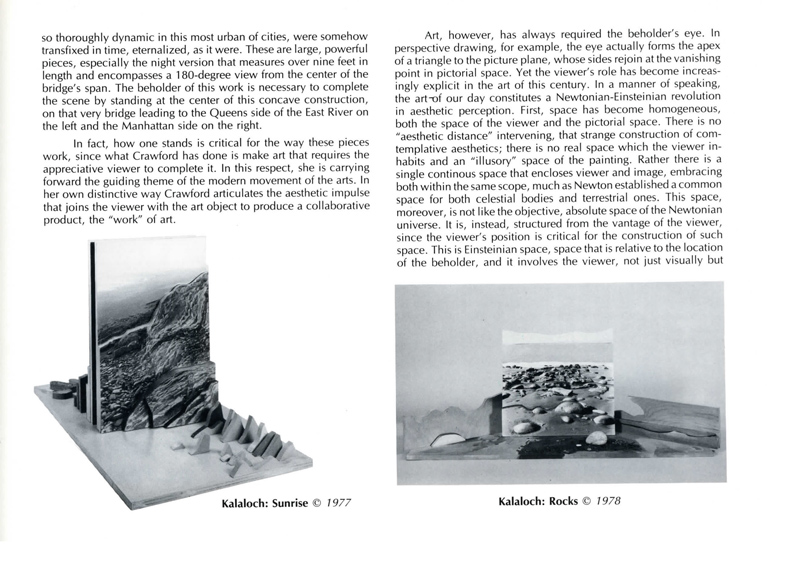

The impulses incorporated into these works took form next in mixed-media landscape constructions. Here Crawford used photographs of shorelines and stones, mirror surfaces, and actual sand, stones and geological shapes cut out of plywood and placed together on a projecting ground panel to extend the space forward in vertical layers. They created movement among the various planes and surfaces, teasing the viewer into entering their space. “Kalaloch: Rocks” (1978) is a particularly successful instance, in which a photograph of a stone-strewn tidal shore leads to a hilly horizon whose contour forms the upper edge of the construction. Cutouts conveying the distant periphery angle outward from the sides of the central photograph panel to embrace the viewer, while a horizontal base panel on which a photograph of rock and actual rock are cemented to the collage surface extend the shore forward toward the viewer. The work has the strange effect of blurring the boundaries of the landscape, just as they would be were we there. It is not a scene that can be circumscribed, “comprehended in one view,” as Shaftesbury in 1712 decreed for painting. Instead one is drawn close to the work and, while looking into it, moves right into that very landscape. “Kalaloch: Sunrise” (1977) is another mixed media construction from the same period that is a completely free-standing, two-sided, omni-facial piece that not only extends the space of the work forward to the viewer, but requires the viewer’s movement to realize the temporal sequence that relates the two sides. These are landscapes in w hi ~ h one might wander about freely, worlds for the body as well as the imagination to experience.

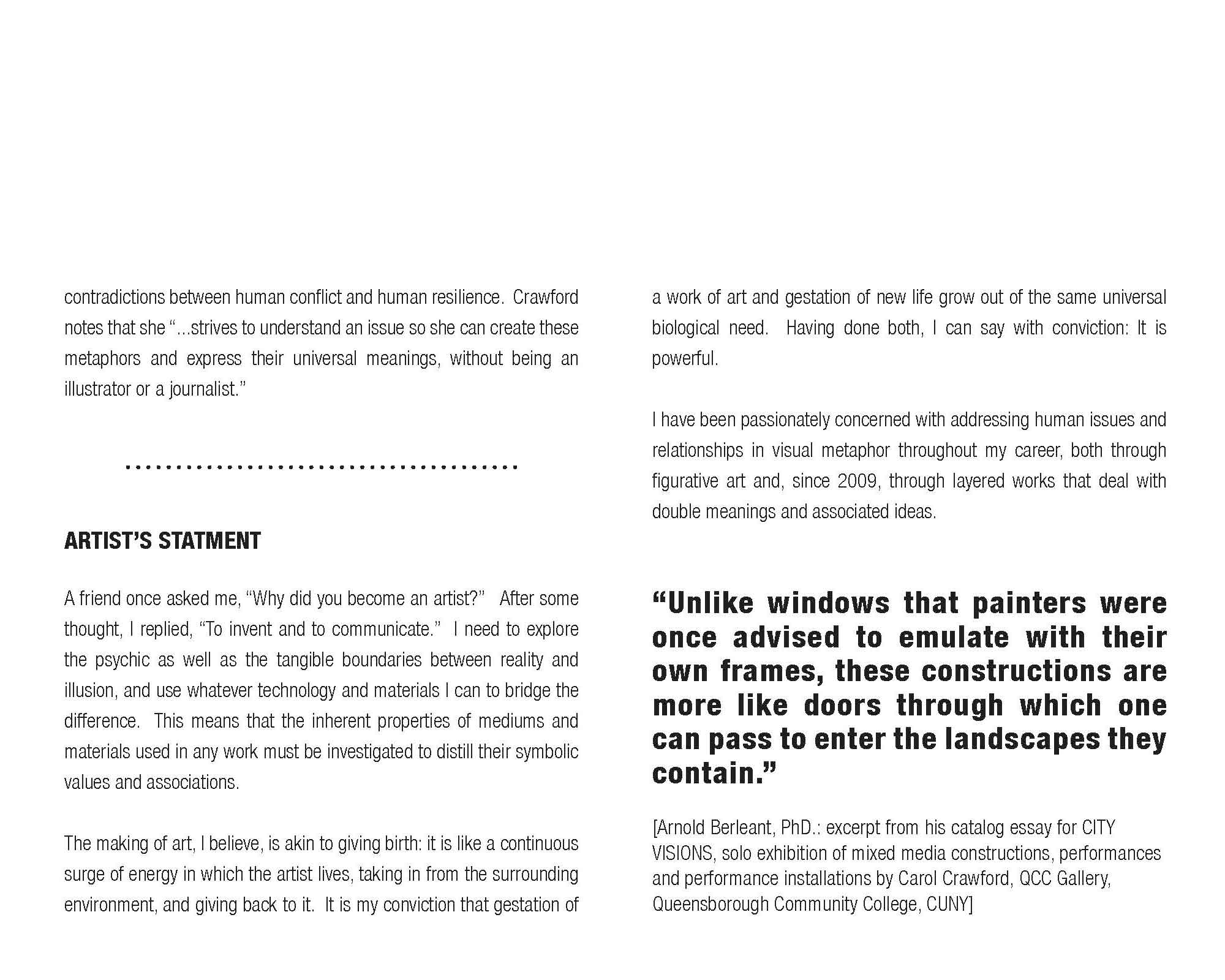

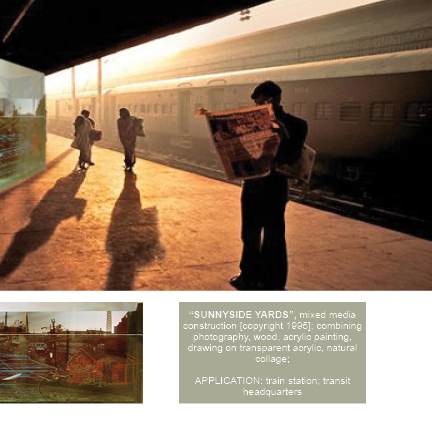

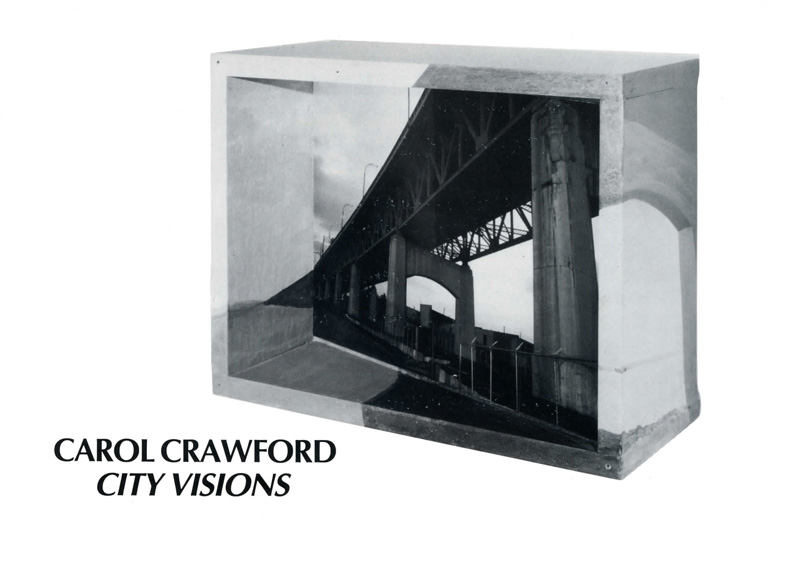

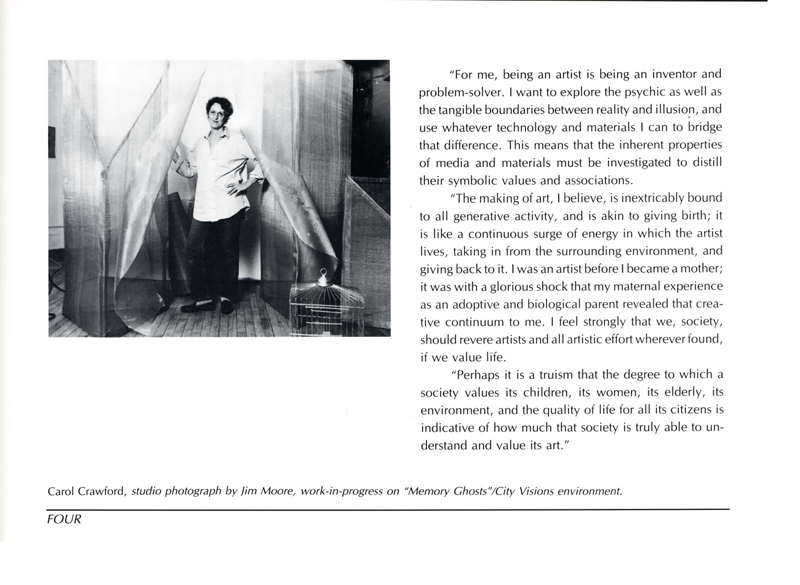

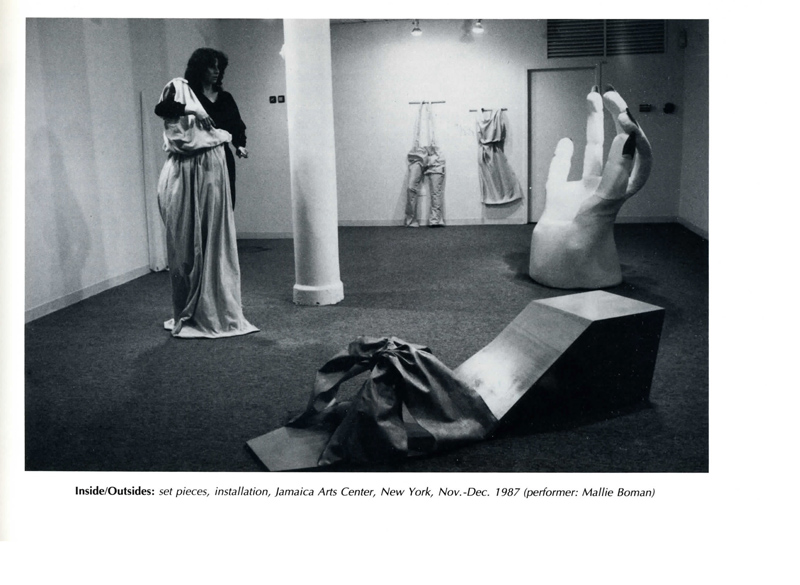

The mix of photographic images and three-dimensional constructed imagery used in these constructions evolved during this time to become props in several performance pieces, in which images, moveable elements, and real objects inhabit space in which the ground plane has become the stage, a landscape which the performer actually enters. Moreover, Crawford’s landscapes are not limited to the natural environment; she is equally fascinated by the sharply different appeal of the urban industrial scene. The installation, City Visions, reflects that interest. In this work three to four hundred photograph s of industrial and highway views of New York City are projected onto three-dimensional constructions made from silver aluminum mesh and aircraft rods, seven to eleven feet high, whose argentine gloss creates kaleidoscopic surroundings of urban images into which visitors can walk and sit, becoming part of the occasion.

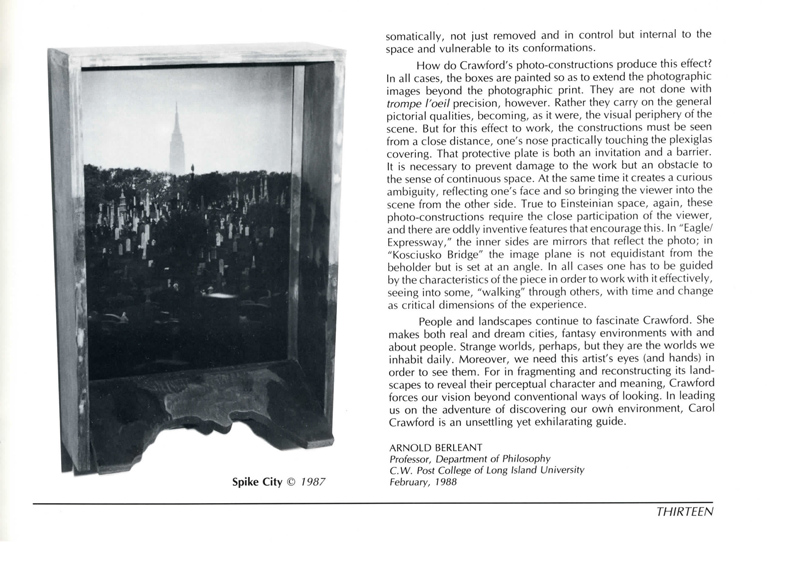

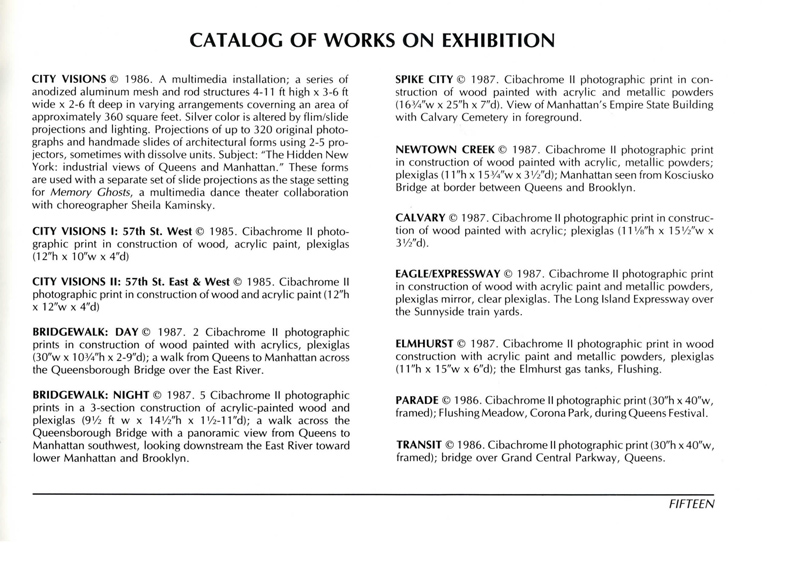

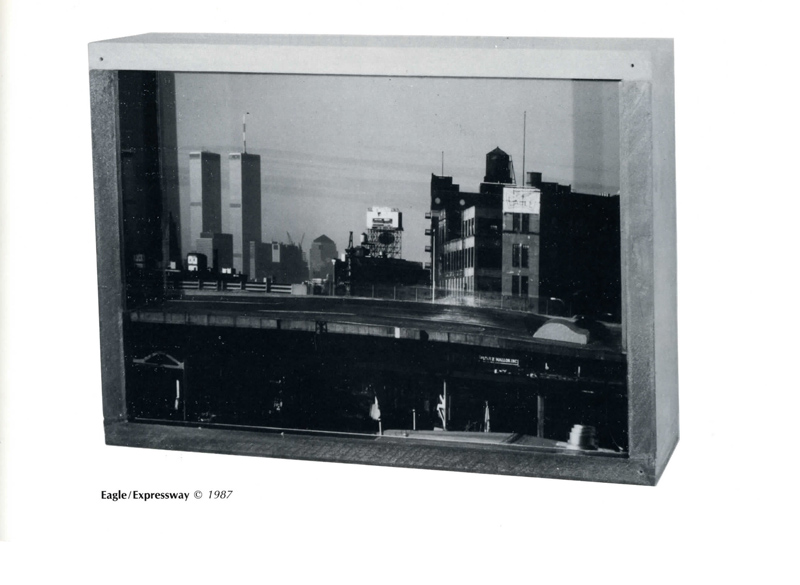

Once Crawford brought the viewer to inhabit her works, she elaborated that idea in ingenious ways. In the photo-constructions that form the major part of this exhibition, the separate elements have coalesced into box-like enclosures quite unlike the traditional frames which confine and delimit a painting. Those frames have been transmuted here into their opposites, extensions of the very landscapes they enclose, so that instead of circumscribing the landscapes they lead them out to the surrounding space. Unlike windows that painters were once advised to emulate with their own frames, these constructions are more like doors through which one can pass to enter the landscapes they contain . “Calvary” takes the viewer along the cast iron fence that defines the desolate border paralleling a cemetery, drawing us into a stern dialectic between the habitations of the urban living and the urban dead. “Elmhurst” gives us a different dialectic yet no more cheerful, this time between the dry brown of winter and the equally austere waning afternoon light of summer. In still another of these pieces, “Newtown Creek,” a steely-surfaced industrial waterway leads us into an equally somber scene, the stillness of early evening caught by the luminous blues of the Cibachrome II photo. “Spike City” lets us look across Calvary Cemetery, its vertical gravestones leading to the horizon, above which stands another monument, the ethereal silhouette of the Empire State Building against the pale pink pollution of the sky. While the size of these pieces is small, their scale is all-encompassing.

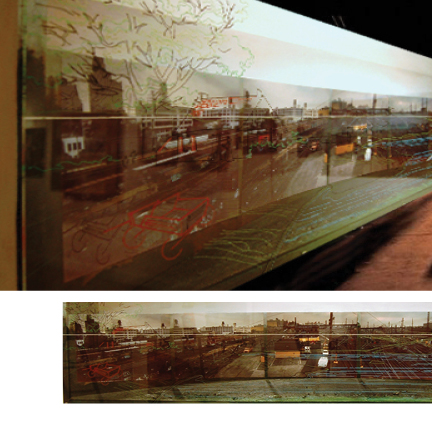

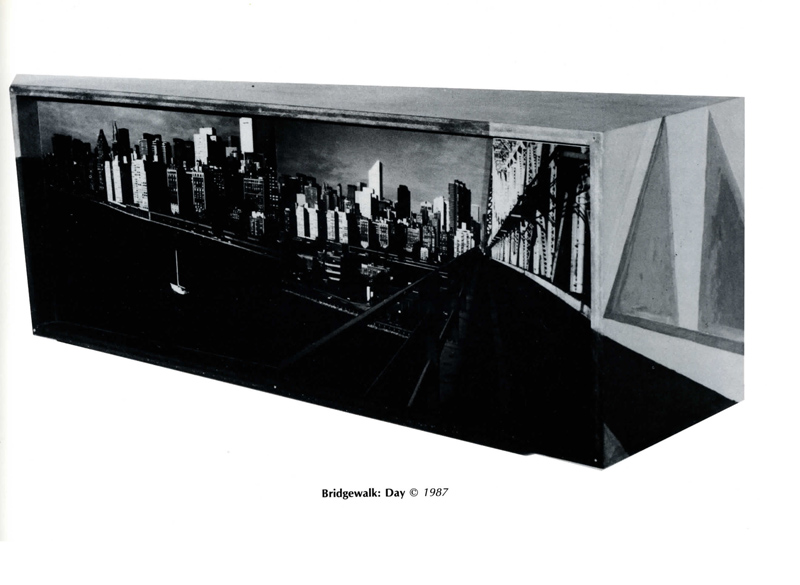

The most ambitious of these photo-constructions is “Bridgewalk,” whose two versions, “Day” and “Night,” convey the urban panorama seen from the Queensborough Bridge with a scope and detail that approaches the original. Both of these related pieces combine deep perspective with an eerie immobility, as if the scene, so thoroughly dynamic in this most urban of cities, were somehow transfixed in time, eternalized, as it were. These are large, powerful pieces, especially the night version that measures over nine feet in length and encompasses a 180-degree view from the center of the bridge’s span. The beholder of this work is necessary to complete the scene by standing at the center of this concave construction, on that very bridge leading to the Queens side of the East River on the left and the Manhattan side on the right.

In fact, how one stands is critical for the way these pieces work, since what Crawford has done is make art that requires the appreciative viewer to complete it. In this respect, she is carrying forward the guiding theme of the modern movement of the arts. In her own distinctive way Crawford articulates the aesthetic impulse that joins the viewer with the art object to produce a collaborative product, the “work” of art.

Art, however, has always required the beholder’s eye. In perspective drawing, for example, the eye actually forms the apex of a triangle to the picture plane, whose sides rejoin at the vanishing point in pictorial space. Yet the viewer’s role has become increasingly explicit in the art of this century. In a manner of speaking, the art-of our day constitutes a Newtonian-Einsteinian revolution in aesthetic perception . First, space has become homogeneous, both the space of the viewer and the pictorial space. There is no “aesthetic distance” intervening, that strange construction of contemplative aesthetics; there is no real space which the viewer inhabits and an ” illusory” space of the painting. Rather there is a single continuos space that encloses viewer and image, embracing both within the same scope, much as Newton established a common space for both celestial bodies and terrestrial ones. This space, moreover, is not like the objective, absolute space of the Newtonian universe. It is, instead, structured from the vantage of the viewer, since the viewer’s position is critical for the construction of such space. This is Einsteinian space, space that is relative to the location of the beholder, and it involves the viewer, not just visually but somatically, not just removed and in control but internal to the space and vulnerable to its conformations.

How do Crawford’s photo-constructions produce this effect? In all cases, the boxes are painted so as to extend the photographic images beyond the photographic print. They are not done with trompe l’oeil precision, however. Rather they carry on the general pictorial qualities, becoming, as it were, the visual periphery of the scene. But for this effect to work, the constructions must be seen from a close distance, one’s nose practically touching the plexiglas covering. That protective plate is both an invitation and a barrier. It is necessary to prevent damage to the work but an obstacle to the sense of continuous space. At the same time it creates a curious ambiguity, reflecting one’s face and so bringing the viewer into the scene from the other side. True to Einsteinian space, again, these photo-constructions require the close participation of the viewer, and there are oddly inventive features that encourage this. In “Eagle/Expressway,” the inner sides are mirrors that reflect the photo; in “Kosciusko Bridge” the image plane is not equidistant from the beholder but is set at an angle. In all cases one has to be guided by the characteristics of the piece in order to work with it effectively, seeing into some, “walking” through others, with time and change as critical dimensions of the experience.

People and landscapes continue to fascinate Crawford. She makes both real and dream cities, fantasy environments with and about people. Strange worlds, perhaps, but they are the worlds we inhabit daily. Moreover, we need this artist’s eyes (and hands) in order to see them . For in fragmenting and reconstructing its landscapes to reveal their perceptual character and meaning, Crawford forces our vision beyond conventional ways of looking. In leading us on the adventure of discovering our own environment, Carol Crawford is an unsettling yet exhilarating guide.

ARNOLD BERLEANT

Professor, Department of Philosophy

C. W. Post College of Long Island University

February, 1988